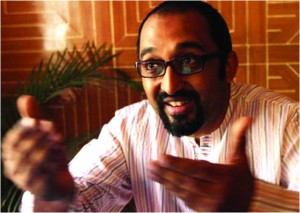

Mosharraf Zaidi barrels his Honda City down Jinnah Highway on this spectacularly hot summer afternoon. His passenger, one Dr. Nadeem ul Haque, is late for a meeting at Islamabad Club. Zaidi serves as the Campaign Director for Alif Ailaan, a project funded by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development. Zaidi believes the education crisis in Pakistan is a political problem and aims to position it as such.

Fewer than half of Pakistan’s children complete primary education, most lack basic mathematical skills, and the percentage of our annual GDP spent on education is significantly below the regional average. Of the nearly 1.1 million government-paid teachers, nearly 200,000 don’t show up to schools. Many of those enjoy this liberty because of highly politicized, and largely unchecked, hiring processes. This lack of accountability presents a significant aspect of the larger education crisis in the country. “Part of fixing the education system involves systematically dismantling the network of influentials that protect and perpetuate this bureaucracy,” says Zaidi. “We must ensure quality teachers, and scrutinize the quality of the education that they impart to our children.”

Nafisa Khattak, Member National Assembly and one of the leading women parliamentarians of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf, agrees. In a roundtable of prominent parliamentarians, think tank delegates, and media representatives, she raised the issue of teachers as one of the most fundamental aspects of any education system in the world. “Teachers are at the core of a quality education of our children. If we do not have capable, qualified teachers with an innovative, creative approach to teaching, this crisis will remain a crisis.”

Nafisa Khattak, Member National Assembly and one of the leading women parliamentarians of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf, agrees. In a roundtable of prominent parliamentarians, think tank delegates, and media representatives, she raised the issue of teachers as one of the most fundamental aspects of any education system in the world. “Teachers are at the core of a quality education of our children. If we do not have capable, qualified teachers with an innovative, creative approach to teaching, this crisis will remain a crisis.”

Since 2009-2010, the federal spending on education has increased by about 25%. However, in that same period, employee-related expenses have shot up by 247%, a ten-fold increase. This year’s federal budget for education is dwarfed by the 800-pound gorilla known as the defense budget by about 10-fold, whereas the debt-servicing budget is nearly 20 times the education budget. “Ten years down the line, the best way for us to reduce our debt servicing, lower our write-offs and subsidies, and build a sustainable future is to invest heavily in the education sector now,” believes Zaidi.

Education is dwarfed by the 800-pound gorilla known as the defense budget

Similarly, Shahzad Mithani, Senior Director, Education and Child Development at Save the Children thinks Pakistan’s education systems are far from the mark. “Getting the fundamentals corrected in 2013-2014 should be the aim of this government. What I mean by fundamentals is getting the education system’s house in order by improved management and working on efficiency. Delving into the education sector in Pakistan is like opening a can of worms… you have no idea what all is going to come out; yet we have no choice but to do it.” Mithani too agrees with Zaidi: an increased budget would help the education sector. “However, the question is, is the system ready to utilize these resources judiciously?” he asks. “I am not so sure.”

This begs the question of whether throwing money at a system that is clearly flawed bears merit. Dr. Nadeem ul Haque disagrees, and as one of the foremost economists of the country, he has a unique, bird’s-eye view of the larger problem. “Education without opportunity is useless,” he says. “Operating in this vacuum and throwing more money at a destructive, broken system is not going to fix it. We have to go back to the drawing board. We have to question why things are the way they are.” It is a sentiment echoed by many, including Ahmed Ali, a Research Fellow at the Institute of Social and Policy Studies in Islamabad. Addressing a large contingent of parliamentarians on June 19, he stressed the importance of scrutinizing where and how this money is being spent, and not being complacent, simply because on paper, we seem to have allocated more funds towards education. “We are simply raising the questions”, Ali says. “Our job is to identify where we see discrepancies, so that the elected representatives can take it up in parliament.”

“Education without opportunity is useless”

Dr. Haque is irritated by the sheer volume of issues that plague the education system. “Public schooling is terrible. The cost of books has sky-rocketed, so how are we supposed to inculcate a culture of reading, especially in the poor? Even in the cultural capital [Lahore], where a large percentage of the population is educated, we have five polo grounds, and five golf courses, but close to no public libraries.” For Dr. Haque, the difference has to come from drastically altering the collective mindset and shifting it from a predominantly feudal to modern way of thinking, where respect and basic rights are no longer the exclusive domain of the king, they are distributed evenly among members of the society.

Nearing Dr. Haque’s destination at Kashmir Chowk, Zaidi’s car is cut off by a van that screeches like a banshee, swerves violently, its battered tires clinging to the road and the swarm of passengers desperately clinging to the van itself. “That right there is a great analogy for the education system in Pakistan,” says Dr. Haque with a smile. He isn’t wrong: overburdened, with no clear agenda, running on fumes and misplaced hope, yet no one to stop and fix it.

From The Friday Times, July 12 – 18, 2013 – Vol. XXV, No. 22